Addressing Psych Safety When Leadership Doesn't

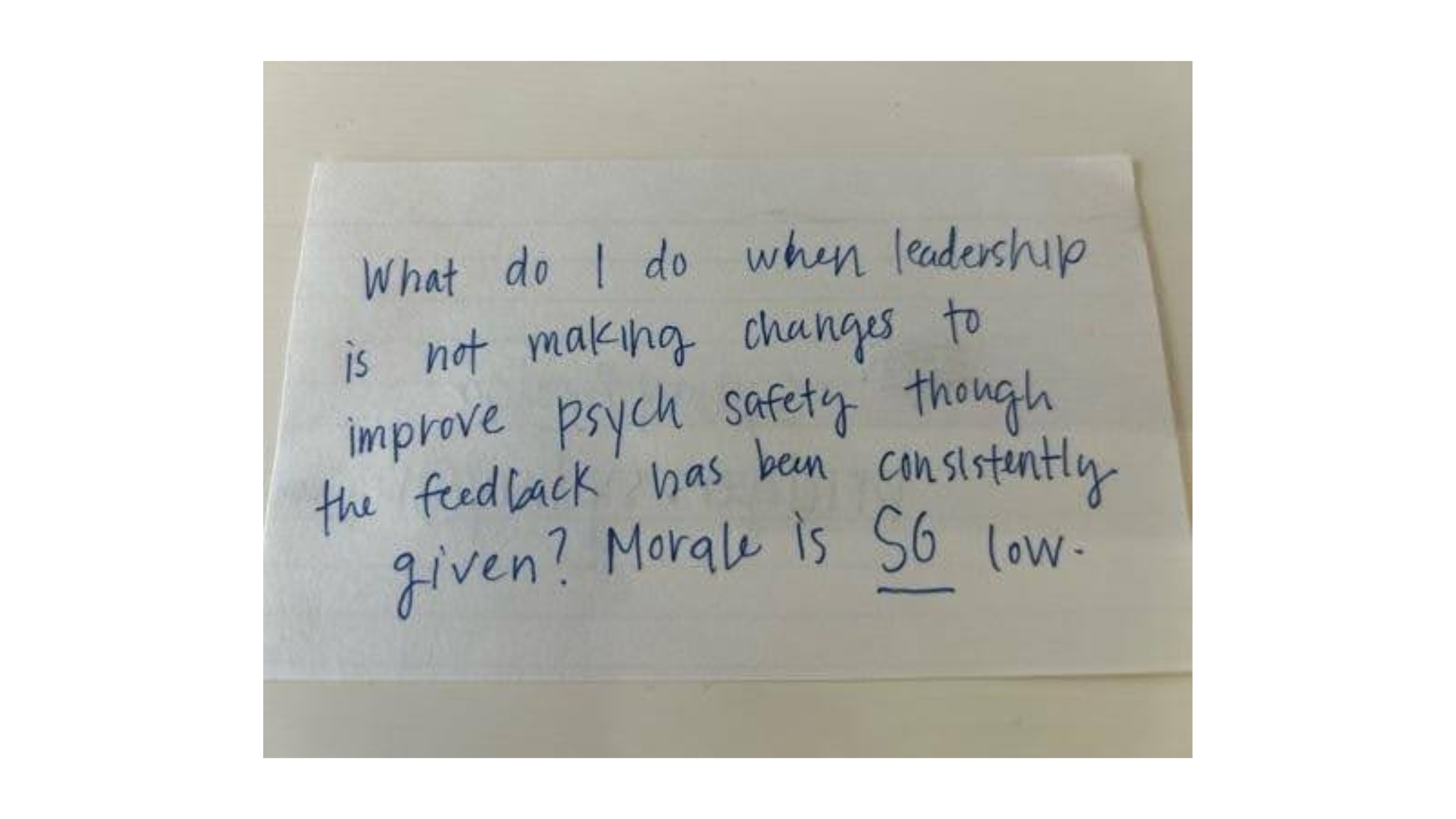

"What do I do when leadership is not making changes to improve psych safety though the feedback has been consistently given?"

We hear this question a lot. I think the most painful part of it is the powerlessness it implies. When you (and others) have made efforts to make needed changes but don’t see results, it’s deflating. That last sentence really says it all.

Because you can’t wave that proverbial magic wand and make your leadership create change overnight, it’s easy to give in to the discouragement and frustration. I get that.

I’d like to offer a few thoughts. These ideas may feel a bit counter intuitive. That’s because when we’re in the midst of difficult circumstances, what is intuitive is to get defensive or self-protective. I suggest while those postures are completely understandable, they are, in reality, just not helpful. Let’s explore a different approach:

1. Beware of the Victim Mindset trap

I have to start by addressing the most tempting, and most dangerous, response to this dynamic – falling into a “Victim” mindset. When things get stressful and you start to feel powerless, falling down this rabbit hole is one of the most natural and easy reactions we humans tend to have. You’ll know you’ve fallen into this trap when you hear yourself thinking or saying things like I wish I could ___ or It’s not my fault that I can’t ___ or I guess I have to ___. The essence of the victim mindset is that when we’re in it, we see ourselves at the effect of someone or something else. Things happen TO us. Our perception is that power resides outside of us, and in someone or something else.

The victim mindset is a cruel killer of curiosity and hope. Getting out of this trap, or avoiding it altogether isn’t easy, but it’s a game-changer.

Don’t become part of the problem. Here is a basic and critical truth about psychological safety: every single person contributes. When one part of a system goes wrong, the rest of the system can bring it back into alignment or react to it in ways that take the whole system out of whack. When a boss (or anyone else) behaves badly, it isn’t just that behavior that creates a problem. The responses of everyone else are also part of the how the whole system is running.

Maria and Jason are the co-directors of a health care team. They both report to a physician named Chris. Chris is experienced by the team as abrasive, dismissive and rude. Maria and Jason are exhausted, frustrated and worried about the low morale of their whole team. In one of my first conversations with them, I invited them to get curious about the mindset they were operating from. When we zoomed out and started looking at the patterns of the team, we noticed that Maria and Jason did a lot of complaining about Chris – to each other and to the team. Because Chris’ behavior was so hurtful, they felt justified in gossiping about Chris in a way they didn’t about others. After frustrating experiences with Chris, they would text each other memes that captured their feelings about their boss, drop not-so-subtle comments about Chris into a conversation with a team member or even leak their frustration by treating someone else as rudely as they’d been treated.

Maria and Jason were right that Chris’ behavior was damaging the psychological safety of the team. What they hadn’t seen, though, was the impact their ways of reacting to Chris was having on everyone. By going into a victim mindset, they had signaled to the team that no one had power, except for Chris. By modeling this mindset, they were inviting passivity, negativity and reactiveness into the system, allowing it to become the norm. What they hadn’t realized was that their reactions to Chris’ behavior were making more of an impact on the psychological safety of their team than Chris was.

Take ownership of what you can do. It’s easy to focus attention on what you can’t do, or don’t have. Empowerment comes from taking ownership of all the things that operate under your control. When you take full responsibility for what you think, feel, say and do, you will usually find that there is more there than you might have thought.

What are the things that could build your, or another’s psychological safety that are under your control? Could you find a creative way to ask new questions? Could you get more curious about the perspectives of others? Could you be courageous enough to be just a tiny bit more vulnerable and transparent? Could you smile just a bit more today?

One of the more insidious effects of this mindset is how we sort of blindly fall into patterns of behavior and play our part in the dance without even realizing what we’re doing. As an example, Maria described how meetings with Chris almost always go: Maria would ask a question or offer an idea, Chris would respond harshly and then Maria would shut down. Wash, rinse, repeat. They did it over and over. In fact, sometimes Maria would shut down even before the whole pattern would play out. She was so conditioned to shutting down when engaging with Chris, she would sometimes shut down just thinking about Chris. In taking ownership, Maria was able to catch herself and instead, make a choice about how she wanted to respond. She realized that shutting down wasn’t actually her only option.

Name bad behavior as bad behavior. There is a difference between being victimized and living from a victim mindset. One of the reasons we go so easily into this mindset is the need for validation. When something harms us, we often look for validation that our pain or discomfort is real. Choosing to operate from a different mindset doesn’t make you wrong about the offending behavior being inappropriate or even toxic. It probably is. It is important to recognize that your concerns can be true and valid without seeing yourself as a powerless victim of them.

Let’s say you’ve been robbed. You’ve been the victim of a robbery. The sense of violation is real. Your wallet is really gone. Having a victim mindset is saying to yourself “Well, I can’t buy myself any more groceries. My credit cards and cash are all gone” and then living that way. Taking ownership of your situation is acknowledging your anger about it, then calling your credit card company to order a new card.

2. Take another look at the Feedback

Yes, people have given these leaders some feedback. Even so, all feedback is not useful feedback. Before you just check the box and move on to being frustrated or miserable, it’s helpful to take a closer look at whether the feedback from the system has really been what that leader needs to understand the scope and complexity of the real problems.

Clarity, clarity, clarity. Most of us are far less skilled at giving helpful feedback than we think we are. We soften messages to avoid conflict and pain. We hint at things and hope the receiver catches on. We use too many words and bury the real message. Paradoxically, when the content of our message has a lot of intensity, we tend to do a worse job articulating what we want to say.

Do a scrub of the feedback the leaders have received. Did you name things specifically? Did you clearly articulate the impact their behaviors are having? People rarely see themselves as the “problem”. One reason is that we confuse intention for impact. Your leader likely had a good or in their view, more important, intention behind their behavior which either blinded them to the impact or gave them cause to justify the impact.

Don’t leave the juicy stuff behind. Too often, difficult conversations happen better and more completely in our heads than they do in reality. It’s easy to get part of a message out and feel like we’ve communicated the entire thing. When offering feedback to your leader, ask yourself – What else? What has been left unsaid? It’s likely to be the part that was the hardest to say, and often the most important. To be effective, feedback has to be SSC - Specific, Succinct and Complete.

Get Curious. In any feedback conversation, but especially this kind, getting curious and empathetic about how the leader is making sense of your conversation is crucial. What is this sounding like to them? What do they need the most from this conversation? How is this relating to the things that are most important to them? You have your agenda in the conversation. It’s likely that you are offering information in hopes of creating change. Setting that agenda aside to get curious about how the other person is experiencing the conversation is usually a gamechanger. The human brain can detect empathy and curiosity in others and it has a mirroring effect. Be mindful that the ultimate objective of any feedback conversation is learning and curiosity is the gateway to learning.

3. Become a Champion

Psychological Safety doesn’t have to be top down. How do new trends or movements start? They begin in the small, personal interactions between people. In the conversations we have, the videos we share, the posts that we “like”. When individuals inside a system begin to champion new ideas and behaviors, they tend to spread – and sometimes quickly.

Look for hidden opportunities. Yes, leaders have an outsized impact on the psychological safety of a team. AND – one person is still just one part of a system. Even when one powerful person in a system is behaving in ways that instill fear, there are things the others in the system can do that bring balance and stability. How can YOU be on the watch for opportunities to increase safety for others? The little things add up. How could you solicit input from others just a bit more often, giving them voice? How do you react to the failures and mistakes of others, and to your own? In what ways do you increase the sense of belonging for others? Every day, there is an opportunity for you to increase safety for someone else. If you were to pay just a bit more attention, looking for them and seizing them, what might change?

Get the conversation going. If the only conversations about psychological safety are the kind where people are complaining, change the game. Metacommunication is “talking about talking”. The strongest teams are great at it. They talk about how they want to have conversations, how they want to give and receive feedback, how they want to solve problems, make decisions and navigate challenges. It can be as simple as starting a meeting with “How do we want to make sure we hear every voice on this topic?” or “What might keep important voices silent in this conversation? How do we want to avoid that?”. When things go wrong or people don’t keep agreements, including some inquiry into how psychological safety played a role can help you get to the heart of things more effectively and efficiently than playing the usual blame game. We have seen this over and over – just by talking more openly and often about psychological safety, teams improve their perceptions of safety substantially, even when they have a difficult leader.

Become a champion appreciator. Did you know that research suggests that less than ten percent of the positive things we think about others ever leaves our mouths? That means that in a given day, ninety percent of the ways we are appreciating one another stays hidden. What a waste. We also know from research that positive feedback – telling someone what we want them to do more of – is far more effective and motivating than criticism. Have a difficult or toxic boss? Here is a subversive idea: instead of trying to change their poor behavior, focus on building all the other great behaviors instead. The same rules apply – specific, succinct, and complete. It doesn’t have to be a giant production. It can be as simple as “Thank you for catching that thing I missed. You are so great at that” or “I so appreciated that question in our meeting today. Thank you for asking it”. Make it a goal to notice one thing in almost every interaction that you appreciate. Even if you end up just communicating ten percent of it, you can literally change the chemistry of your system. Appreciation generates oxytocin (the trust hormone), dopamine (pleasure) and serotonin (well-being) in both the giver and receiver. In a stress-filled environment, generating these important neurochemicals is what keeps everyone balanced and able to think clearly.

Reflection:

A question to ponder (writing your thoughts down can be really helpful)

- How might my responses to the problem be a part of the problem?

Conversation Starter:

Giving and receiving feedback really well takes a lot of practice.

- How can we practice this more often and increase our skills?

An Experiment to Run:

At your next meeting, start with asking one of these questions:

- What is at stake if we don’t get all our best ideas out today?

- How do we want to make decisions in today’s meeting?

- How can we make sure we get enough healthy disagreement in this meeting today?

At the end of the meeting, take three to five minutes to discuss what you noticed about the meeting and how it may have been different than normal.